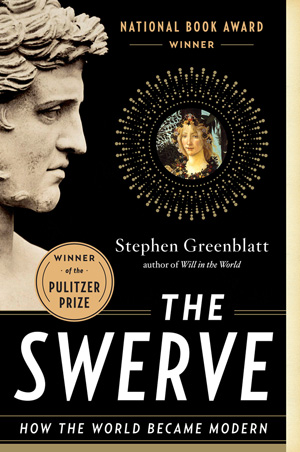

The Swerve, How the World Became Modern by Stephen Greenblatt

In history class we learned that the Dark Ages were, well, dark, and the lights didn’t come back on until the Greek and Roman humanist traditions were rediscovered in the Renaissance. Thus modern civilization officially began.

What I never understood was how the lights came back on? How does a culture that has been actively and accidently suppressed for over 1000 years reappear?

Fragments of the physical monuments of the great civilizations remained even during the Dark Ages. In Rome, citizens were accustomed to the presence of ancient ruins and scavenged accordingly. But the intellectual underpinnings of the architecture were long gone. Oral histories were forgotten, and manuscripts destroyed by book worms, fire, and mold.

But not everyone ignored the traditions of the past. In the 14th C, the scholar Petrarch discovered, studied, and distributed ancient masterpieces by Cicero and others. His work inspired other scholar sleuths. The hunt for lost manuscripts began in earnest.

The main hunting ground for classic works was monasteries. Here monks mindlessly copied the great works and then shelved them for hundreds of years.

In one such remote monastery in 1417, a book hunter and sometime papal court employee Poggio Bracciolini uncovered a copy of Lucretius’s influential poem On the Nature of Things.

Its discovery was the equivalent of a replacing a 40 watt bulb with stadium lighting.

Greenblatt explores how this surprisingly modern poem influenced thinkers from Shakespeare to Thomas Jefferson and took the world in an entirely new direction.

I loved this book— a mini refresher course in Western Civ without the boring lectures and the final exam!