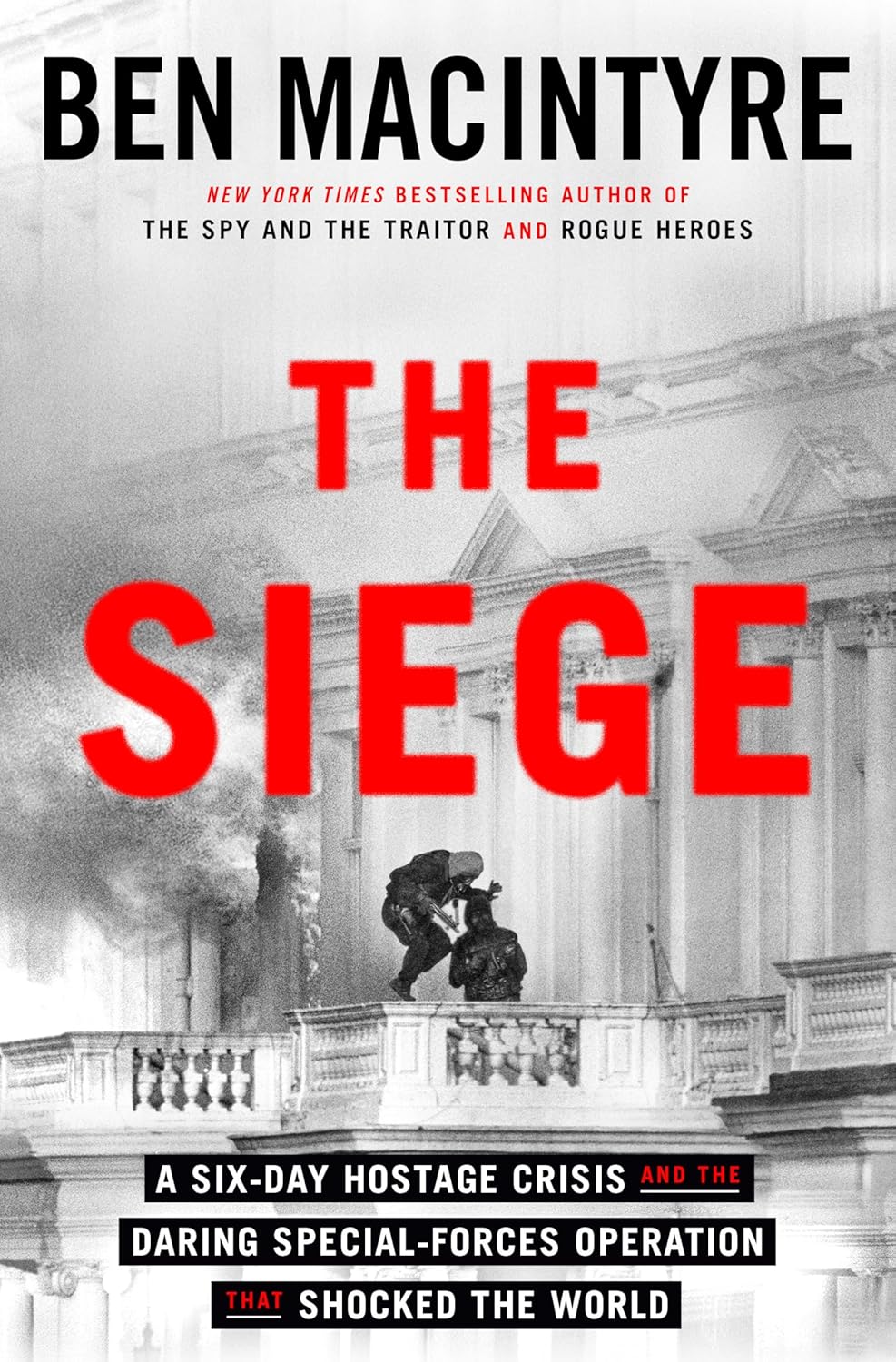

The Siege by Ben Macintyre

On the morning of April 30, 1980, six heavily armed young Arab men stormed the Iranian Embassy in London and captured the twenty-six people on the premises. A few hours later a typed statement in English and Farsi fluttered down to a waiting representative of the Metropolitan Police. The document, signed by the Arabistan Martyrs, referenced the persecution of non-Persians in Iran, made three somewhat unrealistic demands of the British government, and concluded, “Long live Arabistan as an Arab free region.” The police were alarmed but also baffled. Even those with extensive Middle East experience did not recognize the group name and, literally, could not find Arabistan on a map.

It was an inauspicious beginning.

If the British were a bit perplexed, so were the hostage takers. With only the sketchiest of preparation, the young men, who had spent the days before the attack shopping for new clothes, were surprised to find the embassy populated with a number of people who were not Iranian, among them a Pakistani farmer and politician, two BBC employees, the police constable who was posted at the front door, a Pakistani British journalist, and the poor Syrian British journalist who was the only person in the building who spoke the three languages of the occupants, Arabic, English, and Farsi. The staff of the embassy included a few holdovers from the days of the shah and more recent representatives from the new government of the Ayatollah Khomeini, whom the old guard regarded with suspicion.

The hostage takers themselves were a more homogenous group, Iranian Arabs from Arabistan in southwestern Iran. When the shah was deposed, the members of this persecuted minority hoped the new government would recognize their demands for independence, but the ayatollah was no more willing to grant autonomy to the residents of this oil rich region than his predecessor.

Surrounding the embassy were the Metropolitan Police, the Anti-terrorist Branch, armed SAS, police negotiators, a professor of forensic psychiatry, members of the press, and protestors. At other locations, representatives of the government including the recently elected Prime Minister, Margaret Thatcher, kept in touch by phone.

The final shadow participant in the drama was the scheming Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein, who had financed the entire coup just make trouble for neighboring Iran.

Over the next six days, in this dangerous but almost carnival atmosphere, the players’ patience, courage, and cunning were tested.

With his deep research and an eye for the telling details, The Siege reads more like a thriller than a work of nonfiction.

Author of Operation Mincemeat, Double Cross, and A Spy Among Friends, Ben Macintyre is one of my favorite nonfiction authors. I highly recommend his latest work.